A recent insightful comment on Facebook about an OpenFalklands post – ‘Falklands Telecoms: £8 Million Broadband Spend: Sure SA and FIG Under Scrutiny’- resonated with many, and I would like to talk about it further in this post.

“The prevailing notion that telecommunications is a “business activity” rather than an “infrastructure service.” Just imagine if FIG converted power or water utilities into for-profit enterprises—it would only add cost (profit for the owner).

Don’t get me wrong, competition should be encouraged and fully enabled. However, when government capital (hard cash) is involved, there must be a tangible asset purchased, not funds diverted into operational activities that merely support a profit margin…

…Let’s hope Universal Service translates into a community-owned and operated model.”

This distinction matters. As the commentator stated, imagine if the Falkland Islands Government (FIG) were to decide to privatise power or water, turning them into for-profit enterprises. The result would almost certainly be higher prices, driven not by service improvements but by the need to generate profit for shareholders. Yet, somehow, this same logic is routinely applied to telecommunications, even though it is just as essential as electricity or clean water.

Telecommunications underpins almost everything: education, healthcare, transport, commerce, and even the ability of families to stay connected. It is the nervous system of a modern society. Treating it as a profit-first business venture risks misaligning incentives; operators maximise revenue, while communities are left to accept whatever service quality results. Examining some private infrastructure ventures involving water and trains in the UK has sadly supported this view.

The Role of Competition

This is not an argument against competition or privately owned companies. Quite the opposite: where competition is possible, it should be encouraged. Multiple providers bring innovation, price pressure, and consumer choice. By 2028, with several LEO satellite operators entering the market, Falklands residents will finally have alternatives. Poor service will no longer have to be endured, and people can and will switch providers.

However, that same reality raises a fundamental question: why should FIG capital be used to underwrite the operations of a commercial telecoms provider when competition is on the horizon? Public funds should never be diverted into shoring up profit margins. Instead, they should be directed toward building tangible, lasting assets, such as network backbones, 4G/5G base stations, inter-settlement fibre links, a fibre link between East and West Falklands, small data centres and switching equipment that benefits the whole community, regardless of which provider provides retail services using the wholesale community-owned telecommunications infrastructure.

Learning from Elsewhere

The Falklands are not alone in wrestling with this challenge. Many other small or remote communities have already shown how a different approach can succeed:

Faroe Islands (Denmark): With fewer than 55,000 people spread across rugged terrain, the Faroese government invested heavily in a national fibre backbone that is publicly overseen. Private operators then compete on top of that shared infrastructure. The result is some of the best broadband penetration in Europe, despite the islands’ isolation.

Åland Islands (Finland): Here, a cooperative model has been employed to deploy fibre-to-the-home services across the scattered communities. Residents effectively own shares in the network, ensuring that investment decisions are made in the community’s interest, not a distant corporation’s.

B4RN: ‘Broadband for the Rural North Ltd‘ is an Internet Service Provider (ISP) delivering symmetrical gigabit full-fibre broadband to the hardest to reach. As a Community Benefit Society, B4RN prioritises social impact over financial gain. B4RN is all about community. We can’t do what we do without the help of local volunteers, investors and supportive landowners.

Rural Canada: In many provinces, municipalities and First Nations have built and now own regional backbones, while multiple ISPs lease access to serve end customers. The public retains ownership of the “roads,” while competition delivers choice and innovation.

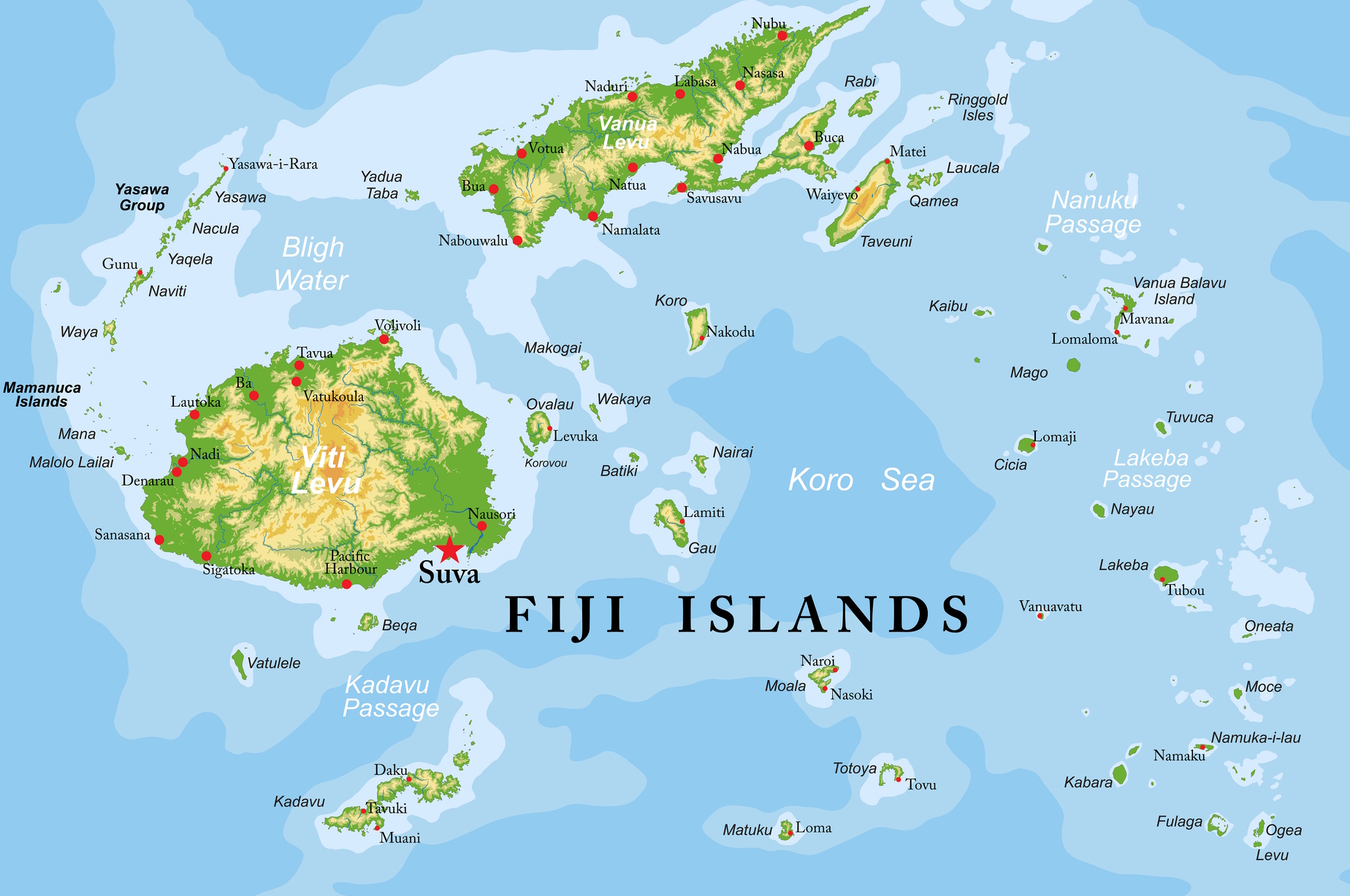

Fiji: Starlink went live in Fiji in May 2024, promising to deliver satellite internet across more than 300 islands. The government licensed the service in late 2023 to expand rural connectivity and strengthen communications during natural disasters. For a country where geography makes internet access notoriously complex, the launch has been described as a breakthrough.

Vodafone Fiji and Telecom Fiji are authorised resellers, and individuals can also apply for kits, though the Telecommunications Authority regulates imports. The hardware itself costs around FJD 1,300–1,400 (£400), with monthly subscription fees varying depending on the selected plan. While this makes sense for businesses and better-off households, it poses a significant barrier for many families in outer islands, raising doubts about the inclusivity of the rollout.

To address these concerns, the government is using the Universal Service Fund (USF) to subsidise Starlink access in underserved areas. Under the first phase, 126 rural and maritime sites will be equipped with Wi-Fi hotspots, solar power kits, and emergency satellite phones, benefiting around 11,000 people. Voucher-based access models will allow communities to share connections, but this also underscores that many cannot afford individual subscriptions.

Challenges remain. Remote islands often lack reliable electricity, installations are complex, and questions persist about long-term affordability and maintenance. Starlink is not a cure-all for Fiji’s digital divide. Still, with careful management of USF investments and fair pricing models, it could become a valuable piece of the country’s connectivity puzzle rather than just another premium service out of reach for most.

The above examples demonstrate that small, remote, or scattered populations can have world-class telecommunications, but only if the foundation is treated as shared infrastructure, rather than a profit silo.

What is a Universal Service Fund?

Universal Service Obligations are often being replaced by Universal Service Funds (USF) in many countries worldwide. A USF is a government-managed program designed to ensure that everyone has access to essential telecommunications and internet services at affordable prices, regardless of their location or income. The idea is rooted in the principle of “universal service,” which emphasises that connectivity should not be a privilege, but a right available to all.

The fund is typically financed by contributions from telecommunications companies, usually calculated as a small percentage of their revenues. In many cases, these costs are partially passed along to consumers through small surcharges on their monthly phone or internet bills. The collected funds are then redistributed to support projects that expand access to underserved areas, maintain affordable services for low-income households, and promote inclusivity for people with disabilities.

In practice, a USF is often utilised to construct broadband infrastructure in rural and remote communities, offer subsidies for affordable connectivity, and provide schools, libraries, and healthcare facilities with reliable internet access. By doing so, it plays a crucial role in closing the digital divide and making sure that no one is left behind in an increasingly connected world.

Addressing the Fear of “A step too far”

Some might argue that in the Falklands, transitioning from an exclusive private company licence to a FIG-owned infrastructure model of some description would be too radical a step to take. After all, it would mean ending the long-standing arrangement where a single, privately owned operator controls everything. Fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) are feelings we all share at one time or another.

But this concern is mistaken and should be firmly relegated to the past. What could be proposed is not the dismantling of the telecoms sector, but rather a rebalancing of roles. FIG would take responsibility for the foundations (the core infrastructure, much like roads or water pipes), while service providers would compete to deliver value-added services on top.

Far from being too drastic, this is precisely how other essential utilities are structured. No one considers it “radical” for FIG to own the electricity grid or the water mains. Telecommunications should be no different. In fact, maintaining the current monopoly under the guise of an “exclusive licence” is the truly extreme position, because it locks the community into dependency on a single provider at the very moment when technology is creating space for competition and choice.

Seen in this light, transitioning to a FIG-owned telecommunications infrastructure model is not a leap into the unknown; it is a natural and rational step toward fairness, resilience, and long-term value for the entire community.

Conclusions

Ultimately, this discussion supports the principle of universal service. But universal service should not mean a few vague commitments from commercial operators underwritten by FIG. It should mean infrastructure that is community-owned and operated, a model in which the public retains control over the foundations. Private companies can then compete on top of that shared base to provide services.

Think of it like a road network: FIG builds and maintains the roads, but anyone can drive on them, families, businesses, and delivery companies alike. No one expects a private company to own the roads and charge a toll every time you leave your driveway. The same principle should apply to core telecommunications infrastructure.

The Falklands have a unique opportunity. With LEO competition burgeoning, including Amazon’s Kuiper network, and significant public capital already being spent on satellite capacity, FIG can adopt a long-term, infrastructure-first approach. Build the foundations, keep them community-owned, and let competition thrive on top.

Such a model would avoid the pitfalls of subsidising a monopoly provider. It would create accountability for capital spending and ensure that telecommunications remains what it truly is: a public utility serving everyone fairly, rather than a profit-driven business extracting from a captive market.

One such community-owned private venture already exists in the Falkland Islands –” Seafish Falklands Ltd exists to enable ordinary Falkland Islanders to participate and invest in the Falkland Islands’ economy.“

As the commentator suggested, let’s hope that when FIG, MLAs, its advisors and the community discuss “universal service,” it translates into just that: a service that is universal in ownership, accountability, and benefits. Islanders expect no less.

Chris Gare, OpenFalklands, September 2025, copyright OpenFalklands

I can see a case for ‘direct to device’ or ‘direct to cell’ in Camp, given how sparsely populated it is – West Falkland has barely 200 people in an area bigger than Somerset – but it’s still useful to have a terrestrial hybrid network for bonding different satellite connections, not only for Stanley, but also Mount Pleasant, home to British Forces South Atlantic, so if one goes down, there’s at least one other available.

This is an example of a hybrid network, albeit a maritime one –

https://marlink.com/resources/knowledge-hub/marlink-adds-starlink-and-eutelsat-oneweb-to-ponant-hybrid-network-for-first-triple-leo-north-pole-service/

An infrastructure-first approach would be like sailing against the wind. SpaceX and Amazon are slated to spend on the order of $50 to $100 billion so that the Falklands won’t need to have much if any terrestrial infrastructure. Just yesterday, SpaceX filed for a 15,000-satellite megaconstellation serving cell phones directly, bringing the company’s licensed total to about 50,000 satellites.