I have now read the two highly redacted public June 2025 ExCo papers, 100-25P and 120-25P, written by the Falkland Islands Government (FIG) and its telecommunications consultants, Cambridge Management Consulting and Incyte Consulting, regarding changes to the operation of VSAT licences in the Falkland Islands. After agreeing with the papers’ recommendations, for the first time in decades, FIG and MLAs are stepping back from the longstanding monopoly initially held by C&W and latterly by Sure South Atlantic (Sure), making space for competition. That’s a huge step by any standard.

Overview

- FIG Signals the End of Telecommunications Exclusivity.

FIG has approved a significant policy shift that opens the door for individuals to self-provide broadband services via VSATs (e.g. Starlink), marking the beginning of a move away from the longstanding exclusive telecoms arrangement with Sure. - Licence Fee Cut from £5,400 to £180.

Following widespread public dissatisfaction, FIG will reduce the annual VSAT licence fee to £180, thus removing a significant financial barrier to alternative broadband access while maintaining a controlled and regulated rollout. - Sure’s Role to Be Renegotiated Amid Legal and Financial Tensions.

Although Sure retains its exclusive licence until 2028, FIG has not accepted its proposals and instead authorised negotiations with them under strict conditions. FIG acknowledges potential legal risks, subsidy requirements, and the need to preserve core services while transitioning to a more competitive market. One interesting quote states: “Sure’s right to make a profit will be respected, but no commitment is given to maintaining current profit levels.”

Thoughts after reading the ExCo papers.

The papers indeed marked a significant step forward in the Falkland Islands’ approach to personal VSAT licensing. The paper proposed a restructured policy and fee model that reflected both technological advancement and evolving legal interpretations.

At its core was a recognition that modern low-earth orbit (LEO) satellite services, now widely available via providers such as Starlink, constituted a functionally different type of connectivity than what was envisaged under the 2016 telecommunications regulatory framework. This change underpinned a shift toward allowing individual users greater autonomy in accessing satellite broadband, subject to compliance with a regulated licensing regime.

A cornerstone of the new policy was the precise definition of “personal use.” This allows individuals or businesses to operate internal communications systems under a VSAT licence, but explicitly prohibits resale, public access, or shared use beyond the licensee. These distinctions were both technical and legal, creating clear parameters to preserve the integrity of the existing exclusive licence while acknowledging public demand for alternative services.

Licensing would only be granted where the connectivity provider, e.g. Starlink, held a valid Electronic Communications Licence (ECL), with a new category, VSAT Broadband Connectivity (VBC), proposed at a provider fee level of £1,800 per annum. Notably, the issuance of individual licences remained paused until at least one such provider, such as Starlink, was formally licensed (estimated by the Communications Regulator to occur by August 2025).

According to the paper, “enforcement” was a crucial component of the regime. Updated application procedures, compliance policies, and public guidance would accompany the reopening of licence applications. Enforcement of licence terms was expected to begin one month after licences became available. This timeline reflected both the administrative reality of regulating a high-demand service and FIG’s commitment to maintaining “orderly market conditions.” The Communications Regulator was tasked with oversight and would monitor consumer behaviour and licence uptake throughout the year to assess both compliance and market dynamics. This issue was discussed in a recent OpenFalklands post, ‘Starlink in the Falklands – a concern answered and an update.’

Legally, the new policy operated within the framework of the Communications Ordinance, specifically the balance between the exclusive licence and lawful exemptions for personal self-provision – FIG is also exempt.

FIG asserted that the approach was both necessary and proportionate, particularly in light of evidence from the 2024 public Starlink petition and the Select Committee’s findings. Importantly, the paper reaffirmed that the Sure exclusive licence remained in force, and the revised VSAT regime did not breach its legal boundaries.

Instead, it provided a narrowly scoped exemption for personal use, justified on the grounds of public interest and technology. The emphasis on proportionality, transparency, and adherence to statutory objectives strengthened the legal defensibility of the proposed changes.

There was, however, a candid acknowledgement of risk. The paper identified the possibility of legal challenge from Sure. To mitigate this, the Executive Council established parameters for future negotiations, including “open-book” (presumably meaning that Sure fully disclose their financials to FIG) subsidy considerations, non-extension beyond the 2028 exclusivity expiration, and no obligation to maintain current profit margins.

Legislative adjustments to the Communications (Fees) Regulations 2019 were anticipated and could be implemented either by a fixed date or notice, allowing flexibility should negotiations or legal processes require more time.

Overall, the paper reflected a technically sound and legally cautious approach to modernising the Falklands’ telecommunications policy. It balanced user demand for accessible satellite broadband with the legal protections of an exclusive provider, introducing reforms in a way that was tightly aligned with statutory principles and administrative capacity.

The foundations laid out in this paper seemed to provide a structured and defensible path for the evolving telecommunications landscape in the Falkland Islands.

Concerns

While I’m optimistic about the direction FIG is taking with the VSAT licence changes after reading the papers, I do think it’s important to acknowledge a few concerns. For one, FIG is still legally bound to its exclusive agreement with Sure until 2028. Even though their monopoly is “loosening,” that could be a bit misleading, as it hasn’t officially ended. FIG must tread very carefully to avoid breaching the contract or sparking a legal challenge with Sure.

If a lot of people switch away from Sure, FIG might end up having to subsidise their continued service obligations, and that could put pressure on public funds. I’ve covered these concerns in a previous post: Holding Islands Hostage Part V: The Enigma of Sure’s Financials . It’s a delicate balance between meeting public demand and not compromising essential services.

Redactions, redactions, redactions.

One aspect that stood out to me in the policy paper was the heavy redaction of some sections.

I understand that FIG needs to keep certain information “commercially confidential” in its public papers, especially when it involves legal advice or ongoing contract negotiations. If FIG is trying to avoid jeopardising talks with Sure or exposing itself to legal risk, I understand that much caution is necessary. However, I must be honest: the extent of the redactions, combined with the missing Appendices, left me feeling a little uneasy.

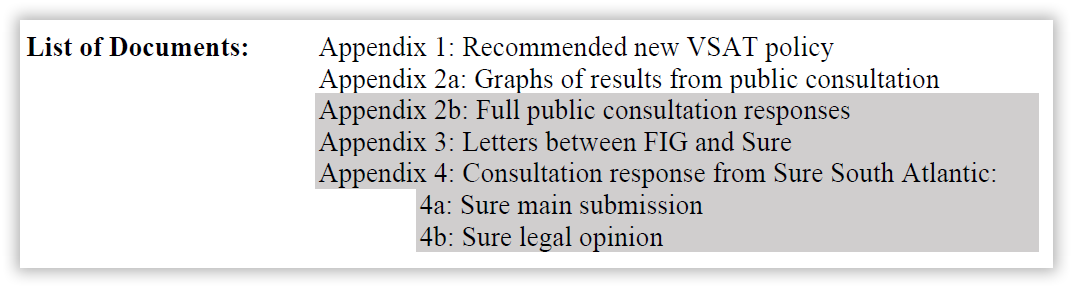

All the missing Appendices are highlighted in grey:

For example, the entire section on the budgetary implications has been redacted. This policy shift could involve public money, whether through subsidies to Sure or the cost of regulating a new system, but we’re not being told how much, or under what circumstances.

What really raised my eyebrows, though, was the complete redaction of Section 6 about Sure South Atlantic’s consultation with FIG, though this is entirely understandable.

There are also redactions in the legal and Camp-related sections, which may hide risks that the public should at least be aware of. It all adds up to a sense that while the policy change is being pitched as a win for the public, not enough is being shared to fully back that up.

I’m excited about the direction FIG is taking, but I’d feel more confident if there had been a bit more openness around the financial and legal realities behind the scenes in the public version of these papers.

Sure’s views?

Reading the paper from Sure South Atlantic’s perspective, their reaction would likely have been a mix of frustration, concern, and strategic calculation. From their point of view, FIG quietly opened the door to competition in a way that undermined their exclusive licence, even if that licence technically remained intact until 2028. While the language in the ExCo paper was careful, the intent was clear: the public wanted alternatives, and FIG was moving to make that happen.

Sure’s biggest concern was probably that this set a dangerous precedent. The original purpose of the exclusive licence was to allow for long-term infrastructure investments with the promise of market protection. Suddenly, FIG appeared to change the rules mid-game, not by cancelling the contract outright, but by using an exception (personal-use VSAT licences) that eroded their market share without fully compensating them. That likely explained why so much of Section 6, which covered Sure’s feedback and proposals, was redacted. It is reasonable to assume that Sure pushed back hard, likely warning of legal consequences or financial losses, which they did, I’m sure!

They may also have felt publicly sidelined, even though they remained the primary provider of critical services such as mobile networks, fixed lines, and the Universal Service Obligation (USO). The report did not outright blame Sure, but it included sharp critiques from the public about slow speeds, high costs, and poor service, especially in Camp. It would be difficult not to interpret this as an indirect indictment of their performance.

At the same time, Sure was likely weighing its options carefully. Legal action may have been, or still is, under consideration if they believed the new policy breached their exclusive licence. But it was also likely understood that suing the government could trigger a PR backlash, especially given how clearly public opinion had turned. This was likely why the government invited them back to the negotiating table to preserve cooperation while implementing significant change.

In short, the paper likely represented, from Sure’s viewpoint, the beginning of a managed decline of their monopoly. They were still being consulted, but the power dynamic had clearly shifted. FIG was trying to keep them engaged through negotiations, but the direction of travel was unmistakably toward a non-exclusive market, whether Sure liked it or not. In my opinion, Sure should choose to cooperate with FIG rather than face the consequences of the alternative.

Conclusion

The June 2025 ExCo papers mark a pivotal moment in the Falkland Islands’ telecommunications landscape. For the first time in decades, FIG has begun to shift away from the long-standing monopoly held by Sure, laying the groundwork for a more open and competitive market. The decision to allow personal VSAT licences at a dramatically reduced fee, while maintaining a tightly regulated framework, signals a bold but cautious response to overwhelming public demand for better, more affordable broadband connectivity.

Technically sound and legally measured, the policy appears to strike a careful balance between respecting Sure’s exclusive rights and responding to real-world changes in satellite technology and public expectations. The introduction of the new “personal use” category and the creation of a new provider licence class (VBC) demonstrate that FIG is not rushing into deregulation, but rather managing change through deliberate legal and administrative steps.

That said, it’s clear this is just the beginning of a complex and sensitive transition. FIG must still honour Sure’s exclusivity through 2028, and any misstep could risk legal action, financial liability, or unintended service disruptions.

From Sure’s perspective, this policy may understandably feel like the thin end of the wedge, the start of an erosion of their market position under the guise of a narrowly defined exception. Yet the public mood is clear, and FIG appears intent on navigating a managed transformation rather than a sudden upheaval. It would be wise to stay at the table and engage in shaping the next phase of Falklands telecommunications. Cooperation, not confrontation, will serve all parties better in the long run.

ExCo’s decision marks an inflexion point, not the end of Sure’s monopoly, but the beginning of its change. FIG has taken a meaningful step toward modern, user-centric policy, with legal and regulatory safeguards in place. The success of this transition will now depend on the timely implementation, transparent governance, and a continued willingness by all parties to engage constructively in shaping the future of the Falkland Islands’ telecommunications..

Chris Gare, OpenFalklands, July 2025, copyright OpenFalklands

I am always apprehensive when I hear words honest and transparency,