On July 1st 2019, the Falkland Islands’ Communications Regulator issued a “Direction to Sure Falkland Islands, No 2019/01a Quality of Service” which requires Sure Falkland Islands to provide data on broadband Quality of Service (QoS), i.e. the performance of the island’s broadband services. All points discussed apply to both fixed and mobile data network performance Quality of Service (QoS) testing.

In Part 2, I will consider eighteen issues that are brought to mind by the Direction, most of which are not addressed in the Direction or the ETSI specifications. The referenced specifications are ETSI EG 202 057-4 and ETSI ES 202 765-4. If you haven’t already done so, please read Part 1 before diving in here.

There is a lot of technical stuff in this post, so if this is not ‘your cup of tea’, please skip to the Conclusions. Let’s jump straight into the eighteen issues!

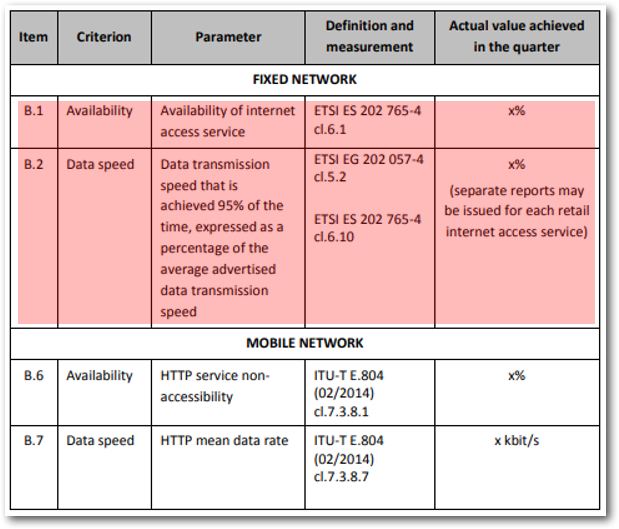

As a reminder, this is what Sure Falkland Islands are being directed to undertake. This is provided in Schedule B of the Direction:

SCHEDULE B: QoS STANDARDS FOR INTERNET ACCESS SERVICES

1. What is “Availability”?

Requirement 8.1 specifies that Sure Falkland Islands provide data on the “Availability of the Internet access service” expressed as a %. This is the % of the time that broadband service is supposedly available over a quarterly period. The devil is in the detail as in what is the definition of “Availability”?

This is not so easy as it first seems. For example, does Availability include unreliable or unusable periods of service known as ‘brownouts’ caused by service performance degradation or not? If so, what level of degradation? Are ‘planned maintenance outages’ included or excluded? What elements of the Sure Falkland Islands’ Internet access network that form the service are included? What if only a % of customers or a single Falkland Islands’ settlement is affected? Etc.

It is relatively straightforward to identify and measure 100% ‘blackout’ level outages, but it is much more challenging to accurately measure and report transient slow-downs caused by congestion known as ‘brownouts’. These are what Requirement 8.2 should be identifying as they determine the Internet performance experience at any particular minute of the day.

Requirement 8.1 and Requirement 8.2 are closely related in practice as they both lie on the spectrum of availability when looked on from a download speed perspective. Availability needs to be defined.

This leads us on to discuss Requirement 8.2.

2. Independent monitoring

It is globally recognised that broadband Quality of Service (QoS), as specified in Requirement 8.2, should be carried out independently of the service provider. All OFCOM monitoring in the UK is carried out using this approach.

There are two principal reasons why this is important.

- To prevent conscious or unconscious manipulation of reported data by the ISP.

- To engender customer trust in published results.

The Regulator has recognised this as an issue:

Independent Monitoring of Quality of Service

Monitoring, through an independent third party, of broadband services may assist in assessing the consumer experience. Throughout 2018 the Regulator has been investigating the viability of independent monitoring in the Falkland Islands. There are a number of issues that have presented themselves which require further investigation in 2019. The primary issue being that international providers of services such as this have no incentive to prioritise contracts with such a small market as the Falkland Islands. The Regulator has made a number of attempts to get quotes for such services but has yet to be provided with any detailed costings.

Due to the Regulators’ perceived difficulties (not discussed in this post), wholly independent testing is not being specified in the Direction as Sure Falkland Islands will be involved by inserting “Monitoring points” in their network. Indeed, if it were independent, no Direction would be required. The Regulators’ 2018 Annual Report states:

Agreement was reached with Sure in Q4 2018 that a number of QoS monitoring sites would be set up across the Sure network. During Q1 2019 Sure will be rolling out monitoring technology to the agreed sites at which point the Regulator will work with Sure to establish output reports that are relevant and easy to understand by consumers. Establishing the means through which the data can be collected on the parameters set by the Regulator is the first step, but there will be no benefit to consumers if the data published doesn’t provide meaningful information on QoS.

I agree wholeheartedly with the last sentence. The Regulator concludes on the web page –

The Regulator is going to continue to investigate options for independent monitoring and seeks to make a report of findings by Q1 2020 once Sure has implemented test nodes through the QoS project

If Sure Falkland Islands installs “test nodes” and/or “monitoring points” (what these are and where they are located is not defined), then no testing regime could be considered independent. The consequence would be that published results would most likely not be trusted by broadband users and other external stakeholders.

If Sure Falkland Islands is to both measure AND report performance QoS data, it’s like putting the ‘fox in charge of the henhouse’. Unless, of course, there is an internal ‘Chinese wall’ which would be impossible to arrange in such a small company.

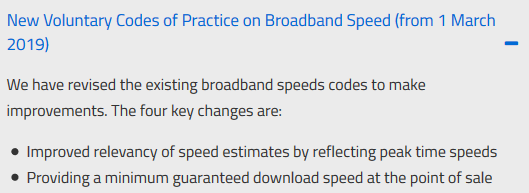

3. The direction is contrary to the UK OFCOM ISP Code of Practice

In the UK, reporting realistically-experienced download speeds are a critical issue that has required active intervention from the UK’s telecommunications regulator, OFCOM. On March 1st 2019, UK ISPs must stop using the exceedingly misleading term of “up to” in their advertising through adopting a new voluntary Broadband Code of Practice.

This “up to” language implies the maximum speed your broadband connection will run at, but in reality, it will run at much slower speeds at certain times of the day due to congestion and high Contention Ratios.

The crucial bit is that ISPs should not use misleading maximum download speeds but give consumers realistic minimum rates at peak times.

The Direction should involve the measurement and reporting minimum download speeds as this is the crucial piece of information the Regulator, stakeholders and consumers wish to know. It currently does not. New initiatives should always follow up-to-date best practices.

4. Consumer compensation for quota use.

The Regulator stated:

Any device connected to a consumers internet service has the potential to use data and therefore needs an agreement with Sure to return this data to the end-user, thus removing the independence of any monitoring as Sure would have to partner with the Regulator on such an initiative. Would the consumer still view this as independent?

The answer to this rhetorical question is no. No agreement with Sure is required to compensate users for the use of their valuable data quota with customer-based independent monitoring. There is an alternative method that has been shown to work.

The total monthly amount of monthly data used for tests is a fixed amount, so the Falkland Islands Government can, independently of Sure Falkland Islands, provide financial compensation to customer participants without Sure’s involvement to restore quotas. This was how the 2010 to 2015 performance QoS monitoring regime worked. This factor should not prevent fully independent QoS testing as long as the amount of test data is only a small proportion of a monthly quota.

Of course, this would only apply in a consumer-based test regime discussed below.

5. Inappropriate use of “averaging”

The ETSI specification referred to in the Direction states:

This indicator evaluates the average download performance when the customer is downloading a file via FTP.

Averaging download speeds, or any other performance QoS metric, over a long period such as a day, week, month or quarter may make sense in a country like the UK where broadband performance is generally predictable and relatively stable over a long period. However, it is an inappropriate concept for use on the Falklands Islands where there is a wide variation of download speeds that can change on a minute-by-minute basis due to satellite congestion.

Let’s say that an average day has 23 hours of a consistent 10 Mbit/s download and 1 hour where download speeds are 0.5 Mbit/s. A reported average download speed over that 24 hour period would be ((23*10)+(0.5*1))/24 = 9.6 Mbit/s. This doesn’t sound too bad, except that it masks one full hour of dreadful performance where customers would be frustrated.

Averaging is an inappropriate concept for performance QoS monitoring and would provide misleading and meaningless results for the Falkland Islands.

6. Quarterly reporting

The Direction calls for a reporting of “average” download speeds “in the quarter”. Although that type of reporting is entirely appropriate for reporting such things as the number of complaints, it is wholly inappropriate for reporting broadband QoS performance.

Download speeds experienced by users vary significantly on a minute-by-minute basis throughout the day depending on the number of concurrent users and congestion on the satellite. Monitoring and reporting must be a continuous real-time, almost minute-by-minute, day-by-day, reporting activity to recognise brownout events that lead to so much user frustration.

7. Day and night periods

Two different periods need to be reported separately as their performance QoS profiles are entirely different.

- Regular daytime traffic – 06:00 to 24:00

- Quota-free night time traffic – 24:00 to 06:00

This is not discussed in the Direction, though it says that different package download speeds may (Should be ‘must) be reported separately. Why was the quota free-free night time period not mentioned in the Direction?

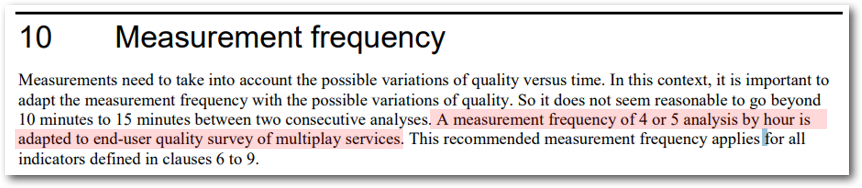

8. How often do individual monitoring tests need to be run?

The ETSI specification suggests the following frequency of running the test.

The measurement frequency 15-minute intervals recommended is far too infrequent to identify and capture ‘brownout’ events. The accepted approach for running QoS performance tests is to undertake an analysis every several minutes to capture fast-moving changes of speeds in times of high congestion. This will always be a compromise between the accuracy of reporting against the amount of data used. Using FTP as the metric is a data hog and not necessarily appropriate. Any form of QoS performance tests will generate terabytes of data that requires special software to condense and report into a way that stakeholders will be able to understand.

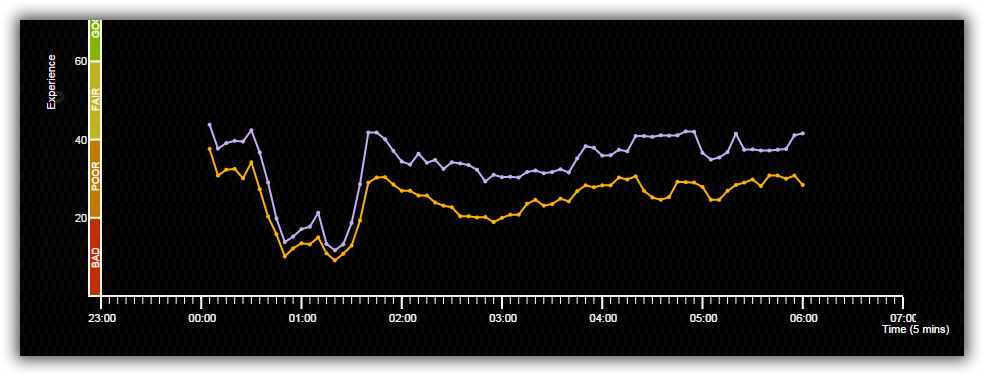

Minute by minute measurement clearly shows periods of brownout events

Minute by minute measurement clearly shows periods of brownout events

Data with this level of time granularity will clearly show blackout and brownout events. Investigation can then be undertaken to understand the cause and maybe implement changes to correct. This should be the principal objective of QoS testing.

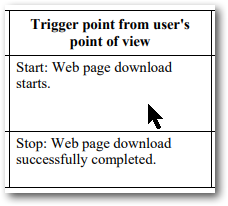

9. Size of the FTP test file

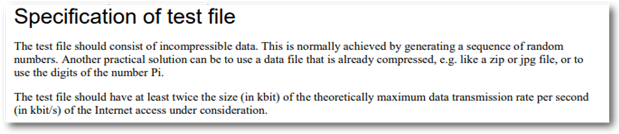

The ETSI specification defines the size of the test file, as shown below:

This represents naively simple guidance. Using this guide to measure an individual FTP download stream, the size of the recommended file (for a Gold package say) should be a minimum of 5.25 x 2 = 10.5 Mbytes. Note: This would vary depending on the broadband package. The issue is that the FTP protocol can take a few seconds to reach maximum download speed, thus increasing the amount of data downloaded needed to get an accurate result significantly. So, if the file is not big enough, the results would be highly misleading. This would not be the case with HTTP website testing.

Let’s say the test was run every 15 minutes as discussed in the ETSI specification, then the amount of data downloaded in a month would be 10.5 x 4 x 24 x 31 = 31.2 Gbytes. If run every minute to achieve the time granularity required, the total amount of data downloaded would be 469 Gbytes.

This FTP-based test would be problematical with Customer-based tests on the Falkland Islands. It would even be problematical for Sure-network based tests. This would not be the case for FTP-based testing in the UK or any other non-satellite country.

The fact is, satellite-connected countries were not considered in these ETSI specifications at all.

10. Sure are not responsible for the performance of the global Internet

Sure Falkland Islands cannot be held accountable for the performance of the rest of the Internet outside of their control as recognised in the Regulator’s statement.

It is also important to recognise that Sure are not accountable for performance across the user experience from start to finish [sic].

Sure Falkland Islands cannot be held responsible for outage issues on the satellite as they do not own Intelsat’s satellite, but it is Sure’s systems that control the amount of traffic going over the satellite that is used to prevent congestion on the satellite so they are responsible for the performance of the satellite link. I have written about this extensively in my post – The enigma of the monthly Internet usage quota.

Sure Falkland Islands are not responsible for the performance of the Internet beyond their UK-based satellite downlink equipment.

However, this is not as easy to define as you would think. Sure Falkland Islands should have a Service Level Agreement (SLA) with their upstream provider, Vodafone, who connect them to the global Internet and they will sporadically suffer from service blackouts and brownout events.

It should be remembered that the April four-hour satellite outage in the Falkland Islands was caused by Sure St Helena and so is out of scope for any Sure Falkland Islands SLA. Or is it? Sure Ascension, St Helena and the Falkland Islands share infrastructure.

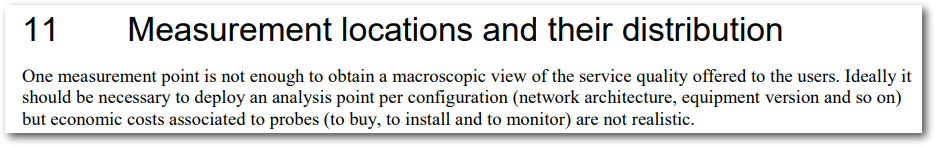

11. Which part of the Sure’s network must be monitored?

There is no discussion about which parts of Sure Falkland Islands‘ network should be monitored in the Direction. I have written extensively about this in a previous March 2019 post – The enigma of tracking the quality of the Falkland Islands’ broadband service – Part2, Looking forward.

There are two possibilities.

In-island Internet access network – excluding the satellite segment

This includes all of Sure Falkland Islands’ in-island network infrastructure including customers’ ADSL access network and Sure’s IP aggregation/routing/switching infrastructure in Stanley but the satellite link.

If an FTP file server as discussed in the ETSI specifications, is located in Sure Falkland Island’s offices in Stanley, then it would only be possible to measure the download speed to and from customers’ premises to Sure’s Offices. This could only be achieved by placing ‘probes’ (more on this later) in selected customers’ homes as the basis of a customer-based test regime if that approach was taken.

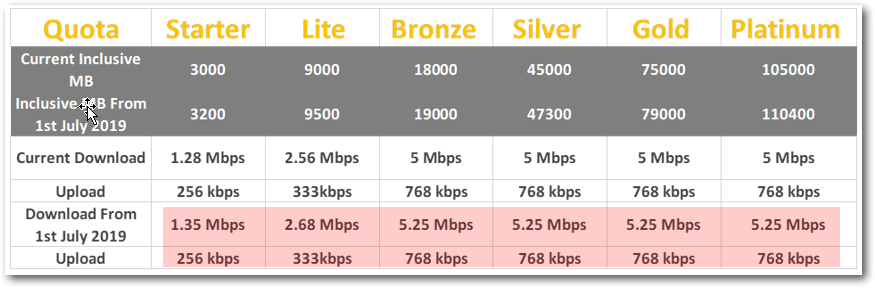

This would only be sufficient to ensure that individually provisioned customer access speeds, determined by the package customers have bought, are correct and as specified as shown in the table below.

As there will be little congestion on Sure’s in-island network, all download speed measurements would be within 99% of the stated speeds unless they have been incorrectly provisioned. Any performance QoS tests undertaken only on Sure’s in-island network will NOT show any service brownout events at times of peak usage caused by congestion or outages on the satellite.

Sure already has a simple speed test on their web site but this uses shareware software.

This limited performance QoS scenario should not be the approach demanded in the Falkland Islands as the data produced would be so limited and not throw any light on the real performance experienced by Internet users.

In-island Internet access network – including the satellite segment

Deterioration in download speeds at times of high internet usage is caused by congestion on the satellite link. Therefore, any test server or probe, as discussed in the ETSI specifications, must be located at the UK end of the Intelsat satellite link if blackout and brownout event data caused by satellite congestion or problems with Sure Falkland Island’s UK equipment are to be identified.

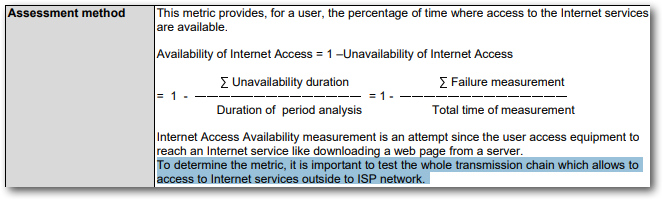

Even ETSI state this. The ETSI ES 202 765-4 specification says that “it is important to test the whole transmission chain which allows accessing to Internet services outside to ISP network”. In the case of the Falkland Islands, this would include the satellite and Sure Falkland Islands’ equipment in the UK.

Clause 6.1, Availability of Internet Access

Clause 6.1, Availability of Internet Access

This should be a mandatory approach for any performance QoS programme if the results are to provide meaningful insight into the performance of the broadband service. The scope of network monitoring should be prescribed and defined by the Regulator in the Direction and not be determined by Sure Falkland Islands.

12. Customer-based or Sure-based tests?

This is a core question that is not discussed in the Direction but is crucial that this is clarified.

Customer-based tests

Monitoring of selected individual customers’ ADSL connections will identify issues in the Stanley and Camp access networks that only affect individual users. Availability of this data will critically help to identify faults and poor performance in Camp and Stanley access networks as well as understanding the impact of satellite congestion on selected individual consumers or businesses.

Sure-network based tests

The ETSI specification assumes this to be the basis of the monitoring. This method of testing performance QoS represents an outmoded technical methodology at best. This is based on Sure Falkland Islands installing and managing FTP servers in their core network and downloading files using FTP, which is monitored by so-called monitoring probes.

This approach represents, at best, only a proxy for what individual customers are experiencing by way of congestion.

13. Where are “test probes” located?

The ETSI specification, as would be expected, is rather vague on this subject.

This is entirely determined by the nature of the performance QoS tests implemented as discussed above. i.e. customer-based or Sure-network based.

Customer-based tests: A ‘probe’, is either a piece of hardware (a modified home router in the case of SamKnows) or software in the case of Actual Experience). These are located on customer premises so that the user-experience of selected individual customers ADSL connections can be measured independently of Sure Falkland Islands.

Sure-network based tests: Several probes or “monitoring points” would be installed on Sure’s core network and/or on Sure’s equipment in the UK although this is not specified in the Direction.

14. FTP or website speed testing?

It is well known that there are considerable differences in user experience between using FTP file downloads and HTTP-based web browsing. So what protocol is used as the basis for monitoring user performance QoS experience is a critical technical decision. The Direction only selected FTP downloads tests which are not the standard approach.

FTP is a dynamic protocol that adapts over time slowly increasing download speeds depending on how much spare bandwidth is available and the level of errors seen whereas browsing websites using HTTP involves downloading many small files and many 3rd party links (advertising etc.). HTTP is a transfer protocol used by the World Wide Web. All these need to be successfully, serially, downloaded before a page will display. Web browsing also includes many individual Domain Network Server (DNS) lookups which FTP downloading does not.

Moreover, if there is a lot of packet loss or jitter, web browsing will be severely impacted (together with real-time services such as Skype) and will become unpredictable and frustrating. This is what happens when there is severe congestion on the satellite. Using FTP download speed testing will provide false confidence that all is well when it is not. Packet loss, jitter and delay metrics are the root cause that determines the level of performance QoS.

The full reporting regime of the ETSI specification which includes numerous technical parameters is shown below, but only the FTP download test has been selected for the Direction though that choice is problematical.

HTTP is more responsive for request-response of small files and reduces round-trips, especially noticeable on high-latency networks as found in the Falklands. It is oft said that FTP’s day has come and gone. The commonly used Ookla Speedtest programme and others use HTTP-based speed testing.

What is interesting is that HTTP-based website testing is what is specified for QoS performance testing of the Falkland Islands’ 4G mobile network in the Directive!

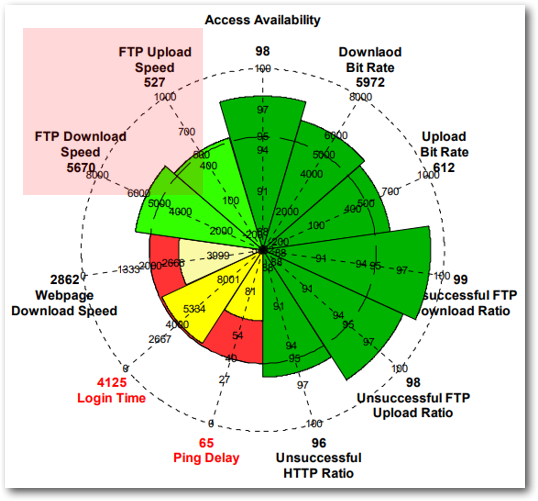

15. “Confident” identification of “culpability”

The regulator states:

It has to be clear in any monitoring system where culpability lies and to be confident where the cause of degradation lies and where the accountability for that degradation belongs.

The devil is the detail, unfortunately. This sounds easy to identify and report, but that is just not the case. For example, let me describe one specific challenge with the islands’ broadband service.

In the UK, Sure Falkland Islands connects to its upstream network provider, Vodafone, who join the Sure-managed Intelsat satellite link to the global Internet. Sure uses Sure-managed equipment such as an IP router/switch to connect to Vodafone’s worldwide IP network. If there is a brownout event that could be assigned to that region of the broadband service, it could be caused by two reasons.

- An overload of Sure’s interconnect equipment – Sure’s accountability

- A brownout in Vodafone’s IP network – Vodafone’s responsibility.

Who is responsible? The picture below shows how this ‘don’t know’ dichotomy could be reported using a “culpability” assignment called ‘Sure-Vodafone’.

Assigning degradation accountability by % in priority order (Actual Experience service)

Assigning degradation accountability by % in priority order (Actual Experience service)

Would Sure or Vodafone be blamed if a Service Level Agreement with penalties were in place? I’ll leave that to the readers’ judgement.

The worst degradation in the picture is the consumer’s home-based Wi-Fi network. Sure Falkland Islands are responsible for their ADSL and Sure-installed routers but not customers’ Wi-Fi networks.

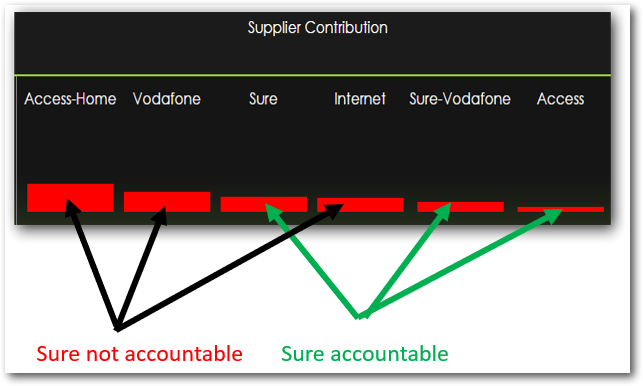

16. “Mandatory minimum standards”

Also, to be found on the Regulator’s web site.

The Regulator considers that it is necessary to direct Sure to provide quality of service reports…

d. to establish baseline data on the current quality of service of cellular mobile telephony services and broadband retail internet services before determining whether, and, if so, what mandatory minimum standards for any of the quality criteria need to be specified.

Has anyone considered the challenge of objectively defining performance QoS “mandatory minimum standards” for “baseline data”? How would this be determined when minimum download speeds could easily be broken by the slightest uplift in usage, causing additional congestion? Would it be Sure Falkland Islands’ fault if it was? No. I am not aware of any country that has implemented such a policy with a public Internet access service. Minimum download speeds provided as guidance, yes, as in OFCOM’s Code of Practice, but not as a “mandatory minimum standard”. No ISP would agree to that.

These are deep waters.

17. “Enforceable penalties”

The Regulator has written:

In due course, these targets can become mandatory standards, with Sure facing penalties if it fails to meet them. Any such mandatory standards would form part of a regulatory Direction on Quality of Service issued by the Regulator with associated power of enforcement.

The Direction also states:

Sure licence Section 26 presents requirements specific to a direction on Quality of Service. The Direction requires the Regulator to establish a QoS regulatory framework and issue a direction to Sure before it can require Sure to monitor and publish information about QoS, and before it can enforce any remedies for non-compliance with QoS targets.

The Sure Falkland Islands’ Exclusive Licence states as its QoS requirements:

The Sure Falkland Islands’ Licence QoS requirement statement

It is so easy for lawyers and non-technical professionals to write clauses about enforcement into Service Level Agreements or Licenses, but it is nearly always impossible to enforce in practice. There are so many ‘get-out’ excuses or Force Majeure reasons to dismiss fault when performance drops below stated metrics.

Enforceable performance QoS targets would be exceedingly challenging to negotiate, implement and enforce even for basic Availability as described in Requirement 8.1.

In my opinion and experience, it would be virtually impossible for Requirement 8.2 performance QoS be enforced through “remedies”. It is neither a workable or an achievable objective for a public Internet access service. Also, is it worth all the effort and cost?

A quote from Network World seems appropriate to bear in mind;

“Consider a cloud vendor’s self-described “industry-leading SLA” of 99.95% that credits your account 5% of the paid-in-advance monthly fee for each 30 minutes of downtime, up to 100% of your fee.

Full refunds are only issued when downtime reaches 10 hours in a month! More importantly, a fee refund is trivial compared to the true potential cost of a 10-hour outage, which could include a loss in sales and customer confidence and result in customer churn.”

These are deep waters – waters as deep as the Mariana Trench I suspect.

18. Mobile network QoS Requirement

Requirement 8.7 of the Direction calls for measuring the “Data speed” of the Falkland Islands 4G service using ‘ETSI-T E.804 (02/2014) QoS aspects for popular services in mobile

networks’.

This states that the “HTTP mean data rate” in “x Kbit/s” is measured (This specification is so old it predates 4G whose data rates would be measured in Mbit/s). This is specified in Clause 7.3.8.7 on page 141:

“After a data link has been successfully established, this parameter describes the average data transfer rate measured throughout the entire connect time to the service. The data transfer shall be successfully terminated. The prerequisite for this parameter is network and service access.”

What grabbed my attention is this specification is that it uses HTTP protocol, NOT FTP protocol as defined in the Direction for fixed-network performance QoS.

This can be seen quite clearly in the table shown below:

This performance QoS specification is so thinly defined that I would hardly call it a specification at all to be honest. Using HTTP-based tests for the mobile service would mean a significant discrepancy and lack of correlation between published performance QoS testing between fixed-line services and mobile services. Using the HTTP protocol would make any comparison of results between the fixed and the mobile networks meaningless. What the reasoning behind this is I couldn’t say and certainly do not understand.

Moreover, because a different protocol has been specified, a completely separate test infrastructure for fixed and mobile testing would probably be required.

Even more curious, Clause 7.3.1.7 on page 54 of the ETSI specification specifies an FTP-based test measuring the “mean data rate” of an FTP download so why wasn’t this used?

No mobile operator could run credible performance QoS tests based on the information provided in this specification and all the other points raised in this post apply to mobile performance QoS testing as well.

Conclusions

As this is a web post and the readers are generally non-technical, I have tried to simplify all technical points raised. However, this is a challenging specialist subject to cover. Broadband performance QoS monitoring must not be entered into lightly, and there are no magic bullet solutions. However, the simple reporting of average FTP download speeds every quarter is an entirely inadequate approach.

There is a lack of operational methodology information supplied in the Direction and ETSI specifications that are appropriate for a satellite-connected country. The concerns raised in the eighteen issues discussed here need to be considered if broadband performance QoS monitoring programme is to be deemed successful for all stakeholders. It is not as simple as reporting of other QoS data such as the number of complaints, fault response times, fault correction times, new customer provisioning time etc.

This is even more important at this time because performance QoS monitoring for the Falkland Islands now involves a high degree of intertwined, political, legal, regulatory, enforcement, licensing, technical and commercial considerations.

It states on the Regulator’s web page – Independent Monitoring of Quality of Service :

Barriers can of course be overcome with a little creative thinking and through maintaining a focus on what the actual objective is – improving customer experience.

I wholeheartedly agree with as an objective, but does the Directive fall short of providing a workable methodology to achieve this?

I’m also at a loss to explain why FTP has been chosen for fixed-network tests and HTTP for mobile tests. HTTP web-page tests would be more appropriate and consume significantly less data than FTP-based tests. The commonly used Ookla Speedtest programme operates using HTTP which uses much less data than FTP-based testing.

As it stands, albeit, with the lack of information provided, the QoS Directive could be considered to be not fit for the purpose and would ask whether it has been thoroughly thought through?

*

Statement: I’d like to state that I was highly involved in the last cycle of broadband performance testing in the Falkland Islands (described here), so I am familiar with the challenges facing a community whose Internet access is via a satellite.

Copyright: August 2019, OpenFalklands